Album review by Neil Hobkirk

We all have favourite film music. Whether absorbed during a movie or savoured separately as an isolated score, the music serves mnemonically, encapsulating dramatic action as we perceive it and summoning it back to mind afterwards. Among my own favourite film scores: Michael Kamen’s The Dead Zone (1983); Mark Isham’s Afterglow (1997); Ennio Morricone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968); Angelo Badalamenti’s The Comfort of Strangers (1990); and Bruno Nicolai’s Eugenie…the story of her journey into perversion (1970). The movie biz calls drama-specific segments of music “cues,” and whenever I listen to these scores on record they indeed furnish memory prompts that unlock distinct moments from the silver screen—or plasma display or computer monitor. When accessed afterwards by ear, cinematic moments unfold once more in the mind’s eye.

But film music can prove memorable in its own right, without experience of the actual movie. Some otherwise unheard scores have become personal favourites once they’ve shown up in film music series: Delos’ Shostakovich Film Series, for example, or Chandos Movies. Complete film music albums from both labels can be streamed on the mammoth Naxos Music Library, which of course also makes accessible Naxos’ own Film Music Classics releases.

Before there was Naxos, there was Marco Polo, a sister label established five years earlier in 1982 to showcase obscure late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century classical music. As more and more labels recorded formerly rare repertoire for release on CD, however, Marco Polo’s unique remit steadily eroded. By now many of Marco Polo’s “discoveries” have resurfaced on Naxos, benefiting from its broader purview and lower price point. And as for those Marco Polos not yet rereleased as Naxos CDs—you can dial them up easily as a Naxos Music Library subscriber.

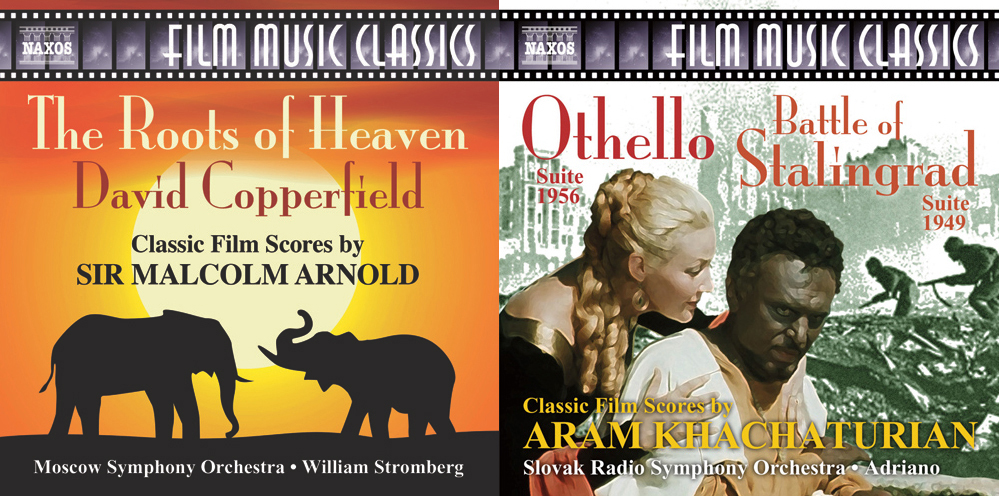

A recent Marco Polo addition to the Naxos Film Music Classics series couples two scores by Sir Malcolm Arnold: The Roots of Heaven and David Copperfield (Naxos 8.573366). Released on Marco Polo in 2001, the disc reemerged just last month. One month later, Naxos this week announced the newest addition: Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s score The Adventures of Robin Hood, a 2003 Marco Polo poised for reissue next month (Naxos 8.573369). (Of all the Film Music Classics titles I’ve enjoyed, I consider another Korngold album the jewel in the crown: a two-CD recording of The Sea Hawk coupled with the score for Deception, released as Naxos 8.570110-11. Sparklingly recorded and exuberantly performed, this Naxos original from 2007 furnishes spectacular, swashbuckling evidence of Korngold’s influential film scoring technique.) Through the Music Library you can already stream the Marco Polo version of Robin Hood, but I haven’t heard it yet. First I’ll let the thunder from the Arnold disc die down in my ears.

Really Roots of Heaven is the thunderous one; by comparison the Copperfield score sounds subdued. In the booklet synopsis Roots (1958) comes off as a high-minded potboiler—a John Huston-helmed Hollywood tale of one man’s quest to protect elephants from poaching. As in his Fourth Symphony two years later, Arnold really puts the percussion section to work, animating the African setting with marimbas, maracas, tom-toms and celesta. The cue “Fort Lamy” matches the percussive exotica with a snake-charming oboe. Arnold has arranged the orchestra to convey vast spaces, and the “Main Title” cue unfolds breezily as though surveying the plains of Africa from above. Braying brass impart a sense of freewheeling adventure.

Throughout the score recur two notably memorable motifs: a romantic string theme evoking the female character Minna, and a thunderous pile-up of tympani and low brass summoning the elephants themselves. Score restorer John Morgan has included Arnold’s “The Great Elephants,” which is the fullest iteration of this colossally impactful motif but did not make the movie. Conducting the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, Morgan’s musical partner William Stromberg honours The Roots of Heaven’s wide variety of mood and colour.

Leaning heavily on recurrence of a single theme, David Copperfield (1969) comes across as less varied and less ear-catching. The melancholic string-heavy signature of the protagonist drapes a veil of gloom over most every cue, with only “Mr. Micawber” and “Mr. Micawber Exposes Heep” emerging into daylight thanks to the flighty clarinet pattern announcing an impecunious yet optimistic secondary character. The last of Malcolm Arnold’s 125 or so film scores, Copperfield too is lovingly restored and conducted by the Morgan/Stromberg team.

A Film Music Classics release from last year, Naxos 8.573389 couples Aram Khachaturian’s Battle of Stalingrad and Othello suites, originally issued on Marco Polo in 1993. In his booklet notes Adriano, the mononymous conductor behind this recording, compares Stalingrad (1949) to Shostakovich’s The Fall of Berlin score from the same year (edited and conducted by Adriano for Naxos Film Music Classics 8.570238). But this concert suite, derived from the score for a two-part patriotic epic, also stirs aural memories of battle music in Shostakovich’s Symphonies No. 7 “Leningrad” (1941), No. 11 “The Year 1905” (1957) and No. 12 “The Year 1917” (1961)—not to mention the Armenian composer’s own bombastic Second Symphony (check out Neeme Järvi’s spectacular Chandos account, CHAN 8945, streamable on Naxos Music Library).

The Battle of Stalingrad suite opens and closes with a noble Russian folk melody; otherwise it’s dominated by martial music enacting the Germans’ steamrolling assault and the Soviets’ stubborn resistance. Encouraged by xylophone and applauded by cymbal crashes, the German incursion sounds vividly horrific. Throughout the music an agitated snare drum controls tension between attack and retreat. There do occur quiet stretches echoing Shostakovich’s war-torn Eighth Symphony (1943), but the mood remains vividly nightmarish as cor anglais and clarinets creep across a seabed of icy strings.

As a suite, Khachaturian’s Stalingrad coheres marvellously; his incidental music for Othello (1956), less well. The complete printed film score was unavailable, Adriano explains, so several cues are missing from the recording. Nonetheless this eleven-part suite yields many splendours, among them Viktor Simcisko’s silvery solo violin in the opening and closing moments. Another soloist, soprano Jana Valaskova, sounds gloriously full-throated and earthy pouring forth the wordless melody to “Desdemona’s Arioso.” More wordless vocalizing comes from the Slovak Philharmonic Chorus, who grace the stately “Finale” cue. Equally splendid are the depth-sounding low brass who, in the score’s most dramatic moments, mimic the moody Moor’s descent into dark wells of emotion.

Typical of the Film Music Classics in sound quality, this disc accords the Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra more than satisfactory sonics, conveying considerable breadth and dynamic range without quite falling into demonstration class. Also typical of the series, Adriano’s notes are comprehensive and closely detailed. Naxos Music Library affords recourse to full notes online—in this case a welcome alternative to my CD booklet’s microscopic print.

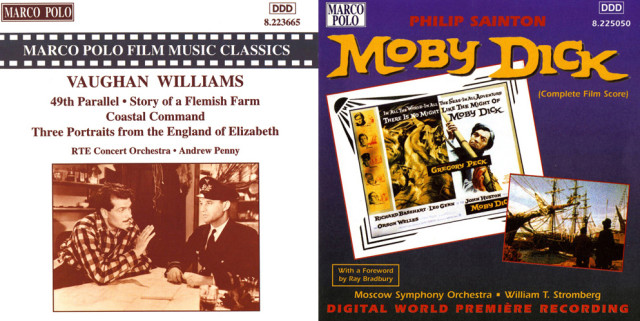

Even better notes accompany a 1995 Marco Polo disc devoted to Ralph Vaughan Williams’ film scores (Marco Polo 8.223665). Penned by Lewis Foreman, author of a superb biography

of composer Arnold Bax, they outline the propagandistic wartime origins of much of the music. Both main works here, the film music suites Coastal Command (1942) and Story of a Flemish Farm (1943), partake of equal parts light and shade.

The tempestuous “U Boat Alert” section of Coastal Command, a dramatized documentary about seaplane patrols, looks back to the blunt, bludgeoning force of Vaughan Williams’ Fourth Symphony (1935). “Dawn Patrol,” on the other hand, inhabits the serene heights of his Fifth (1943), composed in the same period as these two film scores. This cue achieves an otherworldly calm through gently terraced string progressions. Following directly, “Battle of the Beauforts” reverts to bellicose mood, with piccolo piercing and low brass brutal.

Performed like this album’s other works by the RTE Concert Orchestra, Dublin under Andrew Penny—who also conducted Malcolm Arnold’s nine symphonies for Naxos—Story of a Flemish Farm is likewise varied. In “The Dead Man’s Kit” tremolando strings sound fingered like worry beads, summoning an agitated vastness. This hushed, icy, awestruck music points ahead to the frigid world of Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia antartica (1952), a direct outgrowth of his most famous film score Scott of the Antarctic (1948). And the wayward solo violin in “Dawn in the Barn / The Parting of the Lovers” harks back to that rapturous pastoral soundscape The Lark Ascending (1921). Elsewhere the suite dispenses strains of sturdy triumphalism, fitting for this yarn about a valiant repatriation of regimental colours.

Philip Sainton’s Moby Dick is another significant film score discovery (Marco Polo 8.225050) but, like the Vaughan Williams disc, has yet to be reissued physically by Naxos. In the 1990s, two outstanding Chandos albums introduced me to Sainton’s music (on separate discs since reissued as a two-CD set). Twenty years later, logged in to the Music Library, I’m finally hearing his only film music. Not nearly so well known as fellow English composers Arnold, Vaughan Williams and William Walton, Sainton somehow got hired to score John Huston’s 1956 Melville adaptation, screenwritten by Ray Bradbury. He had zero experience composing for the screen.

The Marco Polo recording immediately establishes Sainton’s aptitude. The “Main Title” hits hard with Waltonian wallops, heard subsequently whenever the vengeful Captain Ahab appears. This initial section likewise launches a billowing string theme that recurs during untroubled stretches in the Pequod’s voyage. The most uplifting cue comes with the crew’s first whale sighting, where whooping horns and impetuous tympani mimic the boats eagerly setting forth. But even during the more uplifting passages, ominous signals portend troubled waters ahead. During “Departure / At Sea” and “Journey Continues,” for instance, bleakly isolated piano notes counterpoint the Pequod’s surging progress. And cues tailored to the rageful mammal himself—“Moby Dick Appears” and “The Great White Whale”—are aggressively eventful, massing brass, tympani and piccolo to alarming effect.

For this recording, love has been lavished on the presentation of Sainton’s music. Bill Whitaker’s notes are fascinatingly detailed and are complemented by further notes from John Morgan, Ray Bradbury and Philip Sainton’s daughter, as well as a radio talk by the composer himself. John Morgan and William T Stromberg’s restoration of the complete score presents over an hour of music, none of it filler. (As founders of Tribute Film Classics, Morgan and Stromberg have in fact made it their mission to preserve and record complete movie scores.) And under Stromberg’s direction, the Moscow Symphony Orchestra navigates Sainton’s predominantly rough waters with brash confidence.

The four Marco Polo albums explored so far feature personal favourite composers’ scores for films I’ve never seen and likely never shall. The final disc I’ll highlight inverts this formula: The Bergman Suites (Marco Polo 8.223682) presents music from a personal favourite director’s films, by a composer whose work I don’t otherwise know. Performed by the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra under Adriano and released in 1998, this is a further Marco Polo disc awaiting physical rerelease on Naxos. The music is Erik Nordgren’s; the films, Ingmar Bergman’s.

The focus here falls principally on 1950s scores. Unfortunately Nordgren’s best-known Bergman music, for The Seventh Seal (1957), is absent; according to Adriano’s booklet notes, the printed score could not be found. But music from the celebrated Wild Strawberries (1957) shows up, arranged as a three-part suite. “Emotions” starts with harp, then blossoms into a melancholy string theme padded sparingly with woodwinds and brass. “Memories” and “Dreams” are likewise sparsely scored, with the latter’s haunted atmosphere sustained by vibraphone, horns and harp. Wild Strawberries‘ music, accompaniment to an old man’s disillusioning journey into his own past, sounds more bitter than sweet. “Swindle and Deceit,” main music for The Face (a.k.a. The Magician; 1958), is even more minimally scored for harp and two guitars, with input from tympani and percussion. An enormous gong crash introduces a four-note tympani pattern while harsh guitar interjections and rattlesnake percussion point ahead to Morricone’s spaghetti western scores.

Music for Women’s Waiting (1952) consists of a theme and five variations. Harp opens the romantic main theme, which the strings state fully then share with other instruments throughout the suite. Like most of the Bergman Suites music, “Women’s Waiting” is delicately scored for chamber orchestra, individual players more often than not spotlit. The suite drawn from Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) is strings- and harp-heavy; in fact, “Dangerous Wine” is wholly a harp duet where one player restates slowly and deliberately the soaring string theme from the opening section, “Chaste Love.” Bergman required that incidental music inhabit his films sparingly, and Nordgren’s treats even big, potentially “Hollywood” melodies in understated fashion.

If forced to favour one film music disc for desert island use, I’d pick Walton’s 1944 Henry V as recorded for Chandos in 1990, where Sir Neville Marriner conducts a concert suite incorporating spoken word excerpts (CHAN 8892). With stirring, stentorian contributions from Christopher Plummer and red-blooded virtuosity from Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, this album constitutes a true sonic spectacle. But these five Marco Polo/Naxos recordings are pretty spectacular in their own right; Sainton’s revelatory Moby Dick in particular would be a wise choice for any island.