Album review by Neil Hobkirk

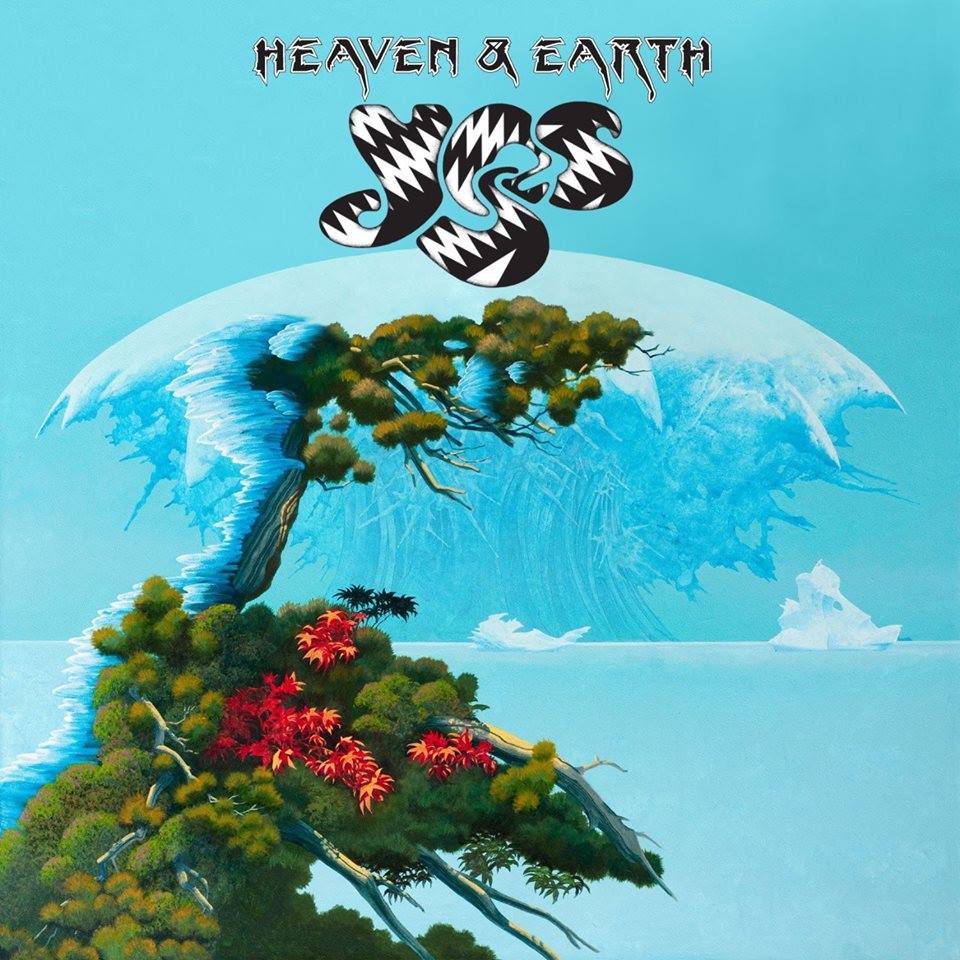

Well, the cover art’s nice.

And the music’s nice too. Or rather, the music’s too nice. Yes, nice music.

So: Yes = nice. But didn’t Yes used to complement the nice with some nasty? On seminal progressive rock LPs like The Yes Album (1971), Fragile (1971), Close to the Edge (1972) and Relayer (1974), and on numerous concert recordings, the band can be heard earning the reposeful world of sunny sublimity limned by lyricist Jon Anderson: alongside his mystical musings and ethereal vocal strains, the other Yes men indulge in instrumental acrobatics whose reassuring precision admits moments of cavalier abandon and crunchy aggression.

On Heaven & Earth (2014), the newest offering in their forty-six-year career, Yes drastically broaden this characteristic disproportion of nice to nasty so that a numinous tranquility prevails, untroubled by threats of musical excitement. For the most part, critics’ words have been withering, often imaginatively so. My favourite quote comes from The Quietus.com, where the album is likened to “an MC Escher house of lethargy…. Every single instrument seems to be quieter than every other instrument, and the songs feel like they’re constantly slowing down, even though we know they aren’t” (review by Nick Reed, 2 July 14). According to tastemakers’ consensus, Heaven & Earth is the band’s worst album; the band itself, a spent force that no infusion of new blood could reanimate.

The newest blood is Jon Davison, most recently lead vocalist for Glass Hammer. Like other devotees of those Tennessee proggers, I greeted the prospect of a Davison-helmed Yes excitedly; his was the voice, after all, that soared throughout the younger band’s recent purple patch of albums, even remaining a presence on their most recent, Ode to Echo (2014). With work recently announced on a yet newer disc, one might well wish that Davison were back in the Hammer fold, for that group continues the tradition of urgently complex, tuneful long-form exploration that most identify with Yes at their best.

Maybe Yes at their best, but Yes necessarily? By now the band has undergone so many major changes in style and personnel that it seems imprecise to identify them exclusively with the tradition they helped start. Yes have confused some listeners by morphing into a straight-up pop group (90125, 1983); substituting an orchestra for their keyboardist (Magnification, 2001); and replacing original singer Anderson with Benoit David, frontman from a Yes tribute act (Fly from Here, 2011). With Heaven & Earth, where David gives way to Davison, Yes offer something different again and elusive of definition—aspirational pop, perhaps?

For if this is pop, it’s trying to be something more. Equally, if this music is prog rock, it’s trying to be something less confrontational, more sedately contemplative. Heaven & Earth seems content to contemplate the distance between the terrestrial world and its transcendence, never conveying the sense of ecstasy that transcendence surely involves. The eight-minute opening number “Believe Again” relates a desire for renewed belief in “a love watching over” and both recounts and cautions against faltering belief (“I lost sight”; “Don’t lose sight”). But there’s none of the mounting drama that animates earlier Yes pieces like “Awaken” (from Going for the One, 1977), elevating the lyrics and listener through a sublime intertwining of contrasted moods and sensations: delicacy and intensity; lightheartedness and gravitas; hope and apprehension. The muted dynamics of “Believe Again” enact no such transformative process.

Instead the song stays resolutely earthbound. From the washy electronica opening, Geoff Downes’ keyboards remain the dominant element. Here and there a bass burbles calmly; throughout the album, in fact, Chris Squire muzzles one of music’s most aggressive bass guitar techniques and concentrates instead on backing vocals. For over a minute, he and guitarist Steve Howe—Yes’ other backing singer—interact dutifully with Alan White’s drums in an instrumental middle section that possibly attempts but definitely denies liftoff. Howe’s spidery fretboard progressions attempt additional elevation, breaking into a triumphant solo one minute from the end. But the effort comes too late. The song disappears and the listener waits for something more.

Something more does not arrive until the last track, “Subway Walls.” Others have commented that this piece, the album’s longest, would have been the logical opener. Certainly the baroque keyboard intro here sounds particularly portentous, and xylophone and tympani-evoking tom-tom rolls impart an extra air of consequence. Moreover, Squire’s grumbly four-string finally emerges fully from the mix, and the Hammond organ makes one of its rare entries on the album. With warmer keyboard sounds overall, and squalling guitar contributions, the track seems to announce “THIS IS PROG!”

But Heaven & Earth as a whole wants to settle for something less rather than reach for something more. Perhaps “Subway Walls” is too prog for the album? With its medium-length songs (only two of the eight fall short of five minutes), this LP aspires beyond pop but holds full-on prog at bay. Taken on its own self-limiting terms, Heaven & Earth is a likeable listen. Throughout, a lexicon of aspiration—“believe,” “beyond,” “transcend,” “ascend,” “mountain,” “beacon,” “path,” “polestar”—finds fit articulation through Jon Davison, the main lyricist. More than Benoit David’s, Davison’s voice is a dead ringer for Jon Anderson’s high-pitched pipes, minus a modicum of elfin inflection. Anderson welcomed an element of play in his singing; he was earnest yet amiable. Davison is earnest.

But the new Jon fits right in, lending an authenticity lacking even from the long title suite voiced by David on Fly from Here. Watch Davison in footage from Yes’ recent concert performances. He looks every bit the wide-eyed wild child handpicked by a group of grizzled oldsters as their collective corpus’ new set of lungs and limbs; a faerie messenger enlisted to convey news of better worlds against a backdrop of increasingly jaded instrumental transactions.

On Heaven & Earth Alan White in particular sounds disengaged: clunkily assertive at best; at worst nearly inaudible in the shadow of the album’s pervasive tambourine. But this low profile suits the genially ambling character of the music: no need for the propulsive sense of adventure the drummer invested in Levin Torn White, his recent instrumental trio date (2011). Geoff Downes drapes proceedings with gauzy electronic trappings, only sparingly spinning out lead lines or touching organ or piano. On stage Downes can replicate Rick Wakeman’s parts, but on record he originates nothing with the Lisztomaniacal zeal that Yes’ most famous keyboardist brought to the studio.

Along with Wakeman’s inventive soloing, Anderson’s angelic singing and Squire’s bellicose bass, Steve Howe’s occasional steel guitar claims a place among the aural hallmarks of “classic” Yes. Sounding mostly reserved on Heaven & Earth, Howe surfaces gratifyingly when he selects the steel for “Light of the Ages.” Familiar from “And You and I” (on Close to the Edge), his eerily leaping, winding lines here chart a course out of darkness into eternal light.

Other pieces appeal to my own idiosyncrasies. “Step Beyond,” with its mildly martial rhythm and percolating keyboard pattern, extends a genial invitation to shed the disguise of everyday pride. “To Ascend,” the outright prettiest track, movingly uses avian imagery to frame a longing for escape and self-reinvention. But my favourite track is the shortest, “It Was All We Knew,” its nostalgic lines “Sweet were the fruits, / Long were the summer days” suggesting a chirpy carpe diem campfire ditty chorused by lotus-eaters.

As an evolution—one among several evolutions—beyond the classic Yes sound, Heaven & Earth succeeds on its own terms. At this point Yes have become to themselves what supergroup Asia (partly co-founded by Downes and Howe) has always been to Yes: an Adult Oriented Rock alternative with certain aspirations. And Roger Dean’s nice cover art remains to Yes what it’s always been: paintings and typography as closely associated with the band as any sound in its career.

[views]